How to answer kids questions about disability

Most parents have felt embarrassed by their child pointing to someone that’s visibly disabled and loudly asking questions. Usually parents try to shush their children, or hurry them along and change the topic. There are better ways to handle the situation though, and there are good, positive ways to answer the questions.

Stay neutral and factual

It’s fine for children to ask questions about disabilities. How we respond, influences how kids perceive disabilities. Not addressing the questions or talking in hushed voices, will communicate that disabilities are shameful, taboo or somehow embarrassing. Instead talking to your child about disabilities can help them gain a better understanding about why some people are different. By keeping your attitude neutral, your kids will feel comfortable being around and interacting with a disabled person.

Disabled people have normal lives and jobs

Help your child accept that the person is different, but that doesn’t mean they can’t do things. For instance, a deaf taxi driver is deaf, can drive you to your destination, and help you load things into the trunk – just the same as a taxi driver that can hear. It’s important kids learn to treat people with disabilities just like everyone else, respectfully.

Answering kids questions on disabilities

There’s always going to be more questions than there you’ll have answers for, but here are some pointers that might help:

- Asking is better than staring

Depending upon the question, it might be appropriate for you to ask the question directly. Most people but would prefer to be asked a question, rather than be stared at. Just remember to be respectful and ask permission to talk about their disability.

“Parents should also teach their children that people have different abilities, both physical and cognitive, but we are more alike than different. They need to teach acceptance and manners. Staring at people with disabilities, avoiding them, or pretending that they are invisible is not okay! Most people would rather answer questions about their disability than be stared at rudely,” – Dr Terry Cumming, Associate Professor in Special Education in the School of Education at UNSW

- I don’t know

There’s nothing wrong with not knowing, and it’s okay to tell your children ‘I don’t know’. You can always offer to search for answers together when you get home. Googling a disability with your kid is a great way to teach them how to educate themselves on unfamiliar conditions. There are lots of child friendly websites with information about autism, Down syndrome, learning disabilities, and other physical disabilities.

Try reading some age-appropriate children’s books about disabilities. “All the Way to the Top: How One Girl’s Fight for Americans with Disabilities Changed Everything,” by Nabi Ali is a bit wordy, but a great book about disability equality (and the introduction of the ADA in the US) for preschoolers and kindergarten children.

- Why can’t that person walk? / Why don’t their legs work? / What happened to their arm?

Try to address this type of question with open and clear answers. Ms Dimmock, CEO of Association of Children with a Disability, recommends responding with ‘They might have been born like that,’ or ‘They might have had an accident’. Factually explain that there are assistive tools that help them, such as wheelchairs, walking sticks or prosthetics.

- How will we speak to them? / Will they understand me?/ How will I tell them?

Communicating with someone that has a visual or auditory disability might seem daunting. It’s normal for children to feel apprehensive about not being understood, or being able to communicate properly. Calmly explain to them that there are many ways to communicate, that the other person can still understand you. Reassure them that they’ll be able to manage, and to just speak normally.

Remember, that every deaf or blind person is different, with different levels of disability, assistive technology and communication preferences. Don’t give up trying to communicate, and don’t be scared to improvise. The National Deaf Children’s Society (UK) says that people giving up, or saying “I’ll tell you later” is very frustrating. They have some great tips on communicating with deaf children!

- Can I touch the wheelchair / prosthetic

Gently remind your child that they must seek permission first. It is always up to the person with the wheelchair or prosthetic. Even if they are trying to do something that appears difficult. To help explain this, Dr Cummings recommends asking ‘how they would feel about a stranger touching their arm without asking?’.

- Why were they born like that?

The simplest answer may just be to say ‘Everyone grows differently, when they were in their mother’s tummy that didn’t grow’. This can be described in a matter of fact manner, no different to explaining why some people are tall and some are short.

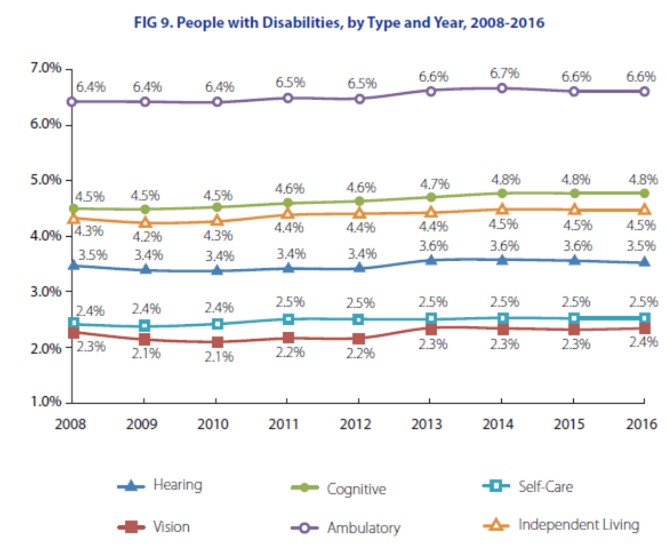

What are disabilities & invisible disabilities?

Usually disabilities are depicted through wheelchairs (car parking spots, bathroom signs, ramps, etc.), but in reality there’s many different types of disability. Disabilities could include hearing or vision problems, cognitive dysfunction, learning differences or mental health disorders. Many of these might not be obvious or easy to see.

That’s how invisible disabilities are defined. An invisible disability is a condition that is not visible from the outside, which limits or challenges movement, senses, or activities.

Disabilities are surprisingly common

More than one billion people, 15% of the population, has some form of disability. That’s enough that most people will know someone with some form of disability. Disabilities can impact people everywhere, and of every age. In the United States, 40 million Americans (12.6%) have disabilities, and over half are working age.

Changing attitudes towards disabilities is essential

Negative attitudes, beliefs and prejudices create artificial barriers for disabled people to get education, employment, health care, and participate socially. Nobody wants to work (or study) in an environment where they’re perceived as less capable, or worse, a burden.

It’s essential that the attitudes of teachers, administrators, and importantly abled children, improve – so as to support the inclusion of children with disabilities into school, and ultimately the workforce.

This is so important that it’s actually one of the nine major recommendations from WHO World report on disabilities.

Source: 2017 Disability Statistics Annual Report, Institute on Disability, University of North Hampshire